Recent advancements in the materials and construction of running shoes over the past couple years have catapulted technological development to the forefront of the competitive runner’s mind when deciding which racing shoe to wear. No longer does it really matter what a shoe looks like or even necessarily how it feels, as long as the new technology has been “proven” to make runners faster—preferably faster by a lot. I discussed the problem with that simple linear approach when assessing whether a purported magic shoe would “work” for every runner in my last post, but aside from considerations of how a shoe and its components can contribute to the efficiency and thus probable effectiveness of a runner, I’d like to address the real problem with modern running shoe technology.

(credit: Spira)

And no, I am not about to rant about how certain shoes, like Nike’s Vaporfly 4%, are unfair because they give too much of an advantage compared to traditional racing shoes. I care little about the carbon fiber plate inserted into the Vaporfly foam midsole that many have pointed to as a veritable spring, and thus should be outlawed because the shoe gives runners an unfair advantage over shoes without springs. Fun fact: before Nike with its Vaporfly, Spira inserted actual springs in shoes for a similar bouncy effect. While never banned outright, Spira claimed that it was against IAAF and USATF rules, particularly those about unfair advantage, as a publicity stunt. For the most part, I won’t discuss the exorbitant economics of the shoes, the price tag of which is $250 without tax and as much as 50% more in the secondary market, since retail quantities have been severely limited—all for a shoe that many have claimed doesn’t last much more than 100 miles. And I’m not going to discuss the fact that these new tech-advanced shoes that elite athletes wear and market in marquee marathons are shoes not freely or fairly available to other competitors as stipulated by updated IAAF rule 143.2, like Kipchoge’s Vaporfly Elite or Des Linden’s prototype Brooks Hyperion Elite, thus giving those runners a uniquely custom advantage over others in the race.

The real problem with modern running shoe technology is: what it has done to running. With the introduction of the Vaporfly and the hype that surrounds it, runners, especially competitive runners, have become obsessed with time as a marker of status and quality of a race. Runners are now willing to pay double what they used to for racing flats and expect to run faster when lacing up their new purchase. I cannot count how many runners I’ve heard remark that they expect to PR in their next race after buying the Vaporfly; what’s more, Nike will gladly refund their purchase if the runners are not happy with how the shoes perform, which encourages the “purchase PR” mentality. And what does running a faster time really get 97% of the runners out there? If they are not a threat to win a major championship or break a world or area record, then these runners are usually racing to challenge themselves and others, to see what we’re made of physically and mentally. To meet that challenge we train, recover, improve, test ourselves, and repeat. To adopt then a mindset in which additional significant improvement can be purchased and applied to one’s feet, and all one needs to do is pay more than ever for it, is to diminish what running is. “I might not be capable of running [insert arbitrary time benchmark for a set distance] on my own, but if I buy those shoes, I might be able to.”

Time and distance have always been the two standard measurements of those tests of self in races. The effort and skill of runners can be measured so, since the goal of everyone racing is to cover the distance as fast as possible, or faster than others. There have been attempts to broaden the measurements of racing, such as Age-Graded Percentage, which compares a runner’s time in a race distance to the best ever recorded for a runner of the same age group and gender. The metric seeks to compare the relative performances of runners across ages and genders and not merely by using race time, a nod to the essential biological factors and limits (muscle, hormones, etc.) present in the activity of running. Strava has also made attempts to eliminate the variables among different athletic activities by calculating a Relative Effort that can be compared irrespective of not only time but also terrain, weather, and even sport practiced. However, a universally agreed upon comparative gauge of a runner’s “true effort”—determining the percentage of one’s maximum ability one actually ran in a given race—does not currently exist. And so time, distance, and circumstances are what we will largely continue to lean on when we evaluate the quality of a race.

If new tech-advanced shoes, like the Vaporfly, actually do improve people’s race times across the board by significant margins (spoiler: it’s not guaranteed), the use of these shoes should not change the reality that a race is a display of embodied effort and skill. Racers should still find ways to dig their deepest, focus their attention and will to the organic cycle of improvement described above. If race times of those with expensive tech-advanced shoes simply improve by 4% or more compared to those without, then time becomes an inaccurate measurement of who the better runner truly is. All time-related points of status in the running world begin to mean less and less, if the clear (i.e. not marginal) difference between achieving them and failing to do so is the shoe chosen. Running a marathon in under 3 hours won’t be so special anymore. The Boston Marathon eventually would have to adjust down its qualification times not by a couple minutes but by tens of minutes. We begin to see more the problem in general with attaching the worth of a run to its time. A runner’s effort can get whitewashed by the shoe’s sliding him or her further along the numerical scale of time, and ultimately our ability to measure great races becomes blurred.

Was Eliud Kipchoge’s breaking the world record for the marathon by over a minute at Berlin in 2018 a great race, even though he did so with a customized version of the Vaporfly, which might have enhanced his time by 4% or more? Maybe. Let’s get back to him later. First, let me tell you about an undeniably great race.

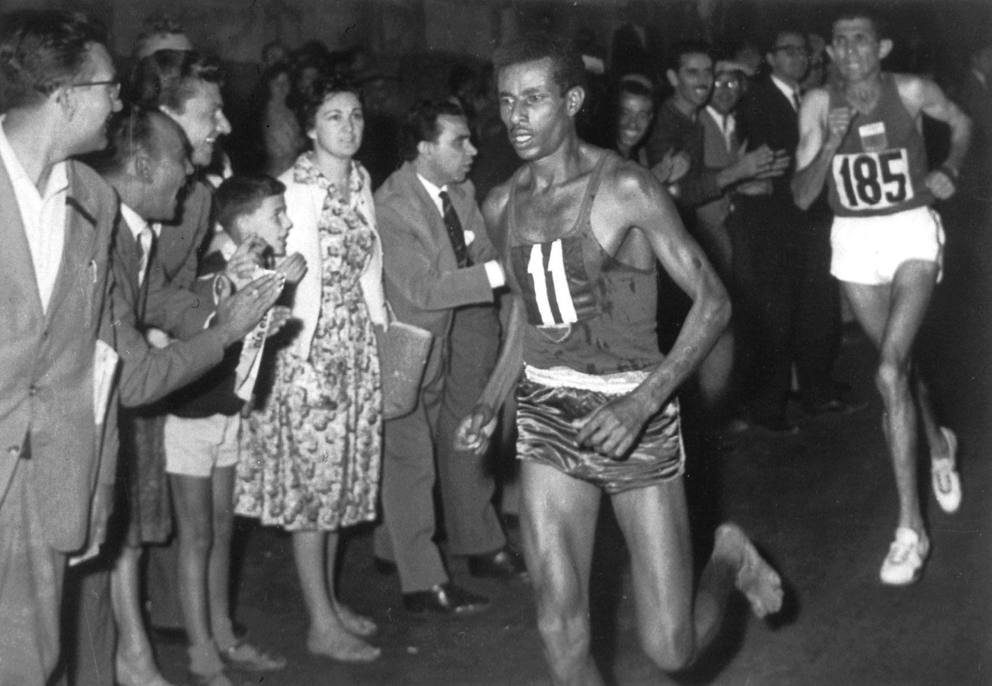

Abebe Bikila, an Ethiopian runner in an age well before tech-advanced equipment or the suspicion of doping, won the 1960 Olympic Marathon in Rome by running barefoot. He chose to go without shoes, because a recent purchase gave him blisters and were uncomfortable. The marathon course covered a variety of surfaces, including dirt and pavement, and Bikila won by pressing a hard pace the second half of the race and surging away from his main competitor, Rhadi ben Abdesselam of Morocco, with about a kilometer left. ben Abdesselam was wearing shoes, and Bikila burst away from him, after running 26 miles unshod. The finishing time by today’s standards was pedestrian, but top class given the circumstances. Bikila finished in 2:15:16.2, a PR by over 6 minutes, an Olympic Record by almost 8 minutes, and a World Record by over half a second. He defended his title in 1964 and ran even faster while wearing a pair of shoes, but his performance in Rome in 1960—time, circumstance, effort—is undeniably one of the greatest running feats of all time.

A running race isn’t much different from other types of races of biological bodies moving themselves over terrain through space and time. There can be various criteria for when a great race occurs, whether it result in a world record or a masterful besting of the competition, or both. I think one criterion for a great race, which should be undeniable and relies heavily on our own spirits as observers of sport, is: we know it when we see it. Even merely hearing about Bikila’s race in 1960 is enough to know. His was an undeniably great race, the type that raises our existence as living beings to a new echelon. The legendary race horse Secretariat offered the world a similarly great race at the Belmont Stakes in 1973. He uncharacteristically charged hard to the front from the beginning and ran away from his only competitor that day, Sham, about half way through the mile and a half race. The furious pace caused Sham to fade and finish last, but Secretariat didn’t slow and won by 31 lengths in 2 minutes and 24 seconds, still the American Record time for the distance. Those who saw it then knew. Those who see it today know. Undeniable.

Imagine that in 1960 Bikila wore an equivalent to the standard racing flat today, with superior cushioning and energy return, while his competitors wore the rudimentary flats they had, and controversy swirled about the possibility that Bikila was able to surge away in the final stretch because he had superior equipment—that he wasn’t actually the superior runner. And what if Secretariat we later learned had spring-loaded horseshoes nailed to his hooves before his masterpiece in 1973, which a couple studies after the fact showed improved running economy in horses by 4% on average? Not so undeniably great anymore, at least not in the same way. Great displays of the potential effect of technology on the performance of living beings? Sure, but it wouldn’t really move us the same, would it?

Technology is only as beneficial to a sport as it enhances the sport. If the sport remains the same, the technology is not beneficial and can be disposed of without loss. If the sport is diminished, i.e. less of or no longer a sport, the technology is harmful. Some relatively complete technological innovations in sport, like the addition of equipment, can elevate the performances of competitors unilaterally. Even some incomplete technological innovations, such as the introduction of better performing materials, can enhance the performances within a sport. These technologies are harmful, however, if their impact on performance is such that the nature of the sport becomes broken.

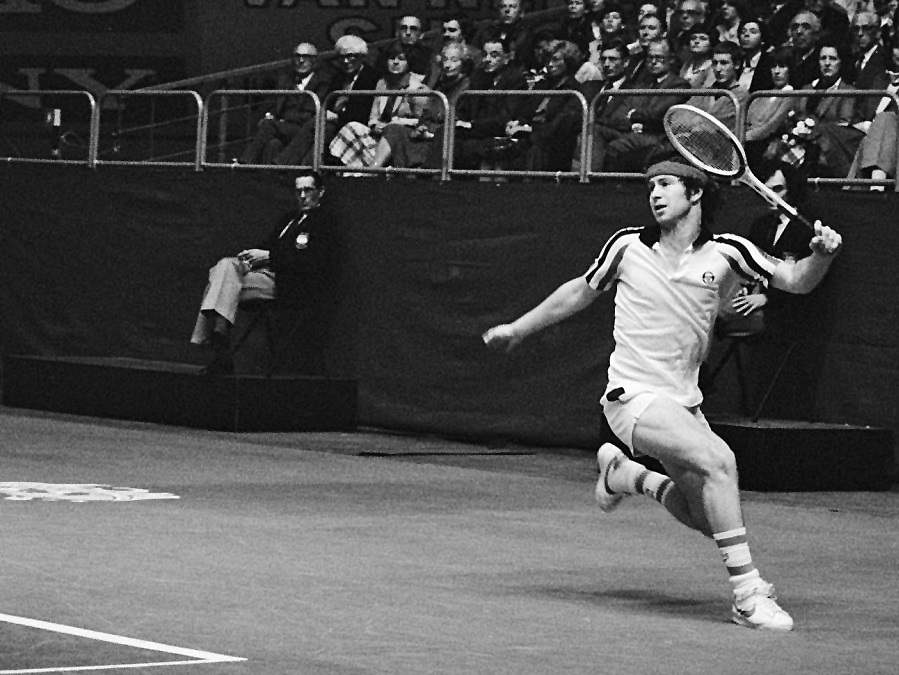

Many other organized sports in the modern era, especially those that require good performing equipment, have recognized the benefit and potential harm of adopting technological innovation and have simply regulated its existence within the sport. Tennis is a prime example. Rackets and their materials have evolved over time and tennis has allowed the adoption of many technological advances, such as a lightweight metal frame or varying applications of court surface (hard, clay, grass, carpet). These technologies have been heavily regulated, though. A racket head can only be so large, as to not allow a player to have so big a sweet spot in the center of the racket, which would make it easier to square up any shot hit his or her way. The length of the racket, too, is regulated. While a racket as broad or as long as the court, extremely light and weight-balanced enough for a player to wield it and without fail make the ball bounce to the other side of the net, would make for an amusing spectacle, it would not yield much sport.

Baseball, too, has nearly innumerable rules on equipment. While the technology exists to make supremely powerful and effective metal bats, Major League Baseball still requires bats be made of certain woods. Of course, too, there are regulations on bat size. There are also regulations about the size of the glove. An outfielder chasing down a pop up with a glove the size of a banner wouldn’t even be amusing but downright frustrating—when he catches it, thus robbing a hit, and when he doesn’t.

Track and field, through the IAAF, also regulates equipment, mostly for the field events that are equipment dependent, like pole vault and the discus throw. The current maximum on the number of spikes allowed in a track shoe is 11. Each spike can be of any length up to 9mm, 12mm in the high jump and javelin. IAAF also outlaws any shoe that has been “constructed so as to give athletes any unfair assistance or advantage,” but doesn’t specify what constitutes that unfair advantage. There are also vague descriptions about what can constitute the makeup of a shoe’s sole, but no rules, at least in the distances and road races, for the material makeup and thickness of the sole. This last gap in the regulation is what the Vaporfly has exposed. As the materials of midsoles advance, the sole of a racing flat has the potential to become more and more like a trampoline and transform running into an activity of bounding as if gravity mattered little. Racing flats used to be stripped down to reduce weight, which indisputably improved running efficiency, but now with the energy return properties of new foams like PEBAX and stabilizing features like carbon fiber plates, shoes could become less like flats and more like moon shoes.

Geoff Burns has pointed out that all running shoes act as springs, technically, as any midsole foam compresses and then expands to some degree (i.e. stores and releases energy, as springs do). His proposition that we regulate the height of “springs” (i.e. midsoles) in shoes is a novel idea that is not without parallel to regulations other sports implement on equipment to preserve the integrity of the activity in contention. There is already a rule on the books about the thickness of soles in the jumping events (IAAF rule 143.5) to eliminate the advantage of the height of the shoe. Perhaps, we should have a similar rule for the soles of running shoes.

I am aware that the technological advancements introduced by Nike with its Vaporfly are likely to become the new normal, and when they do, I might even try racing in a pared-down version of a moon shoe. For all this diatribe against the Vaporfly, I actually think innovation within sport is good and healthy, as long as it stays within the sport and enhances credible performances. Theoretically, I think a shoe through its construction can impede how someone runs, and ideally the shoe would “get out of the way” and allow one full opportunity to achieve one's maximum mechanical potential. Cushioning materials in our age of pavement can help more runners who aren’t Bikila do so, thus expanding the sport. Those materials and their application, however, also have potential to "get in the way" and directly significantly improve a runner’s performance, thus transforming the nature of the sport and rendering achievements like Kipchoge’s less meaningful.

(credit: Nike)

Integral to running is the action of applying force to the ground with feet in order to move forward. Once that action loses its ground feel and becomes more like skipping through squish, then the equipment has diminished running in my mind. When runners splurge because of the assumed magic of a shoe and effectively expect to have purchased an advancement of time in their races, an advancement of status as runners—a path akin to winning at all costs—, running is diminished in my mind. If those who wear the Vaporfly were to say they do so because the shoe makes them feel like their best running selves, or merely that the shoe feels fun and they’re really only running to have fun, I wouldn’t have a problem. But those innocuous intentions are not what has been publicized so far by Nike and its customers.

One advantage of the Vaporfly shoes that no one seems to talk about is the amazing comfort that I believe also boosts performance. Because of better shock absorption, my, soles, feet, and even legs simply feel fresher towards the end of a marathon when wearing these Nikes. Less pain and tissue damage from impact and jarring means better pace at the end. When I ran marathons in racing flats and Adidas Boston, the bottom of the feet felt beat up and inflamed after the races. In the Vaporflys, my feet feel fresher after a marathon than in regular training shoes (Nike Zoom Fly) after a 20 mile training run. I suspect for a masters runner like me, the comfort and lower risk of impact related injuries outweighs any performance gains as the primary reason to race in the Vaporflys. When I first heard of a potential ban, my main concern was comfort, not speed. Full disclosure… I am not particularly light (155 lbs) or fast (2:46). So my opinion is probably not particularly unique.

Hi Robert! Thanks for the thought. Sorry for the delay, since I stepped away from the blog for a bit. Maybe one of these days I’ll post a follow-up, like racing against the past versus racing against the future, since the super shoes appear to be here for good.

Superb Blog, das pure Leidenschaft strahlt … Kaylil Arlan Boatwright

Danke!

Pingback: Sabatilles per “volar”? - xavigallego.enproceso.es

Pingback: Sabatilles per “volar”? - Xavi Gallego